What is the Federal Reserve’s job? The standard answer is to maintain full employment and stable prices. This is what economists and commentators mean when they talk about the “dual mandate.” But there’s a problem—as a matter of law, the Fed’s mandate has three parts, not two.

The Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977 established the Fed’s objectives as we know them today. In addition to job promotion and price stability, the central bank is responsible for “moderate long-term interest rates.” It’s supposed to conduct monetary policy with all three goals in mind.

You almost never hear about the interest rate plank. There’s a tacit agreement among policymakers that this portion of the mandate is redundant. The Fed does all it can for interest rates when it achieves its employment and price stability goals.

As a matter of economic theory, this is a strong argument. Interest rates are prices for capital. These ultimately depend on the supply of and demand for loanable funds. We want markets to price capital such that the last additional amount supplied is just as valuable as the last additional amount demanded. This is a standard efficiency result from basic economics. Markets are good at pricing and valuation. Besides maintaining price stability, meaning a stable value for the monetary unit—prices are denominated in dollars, after all—there’s not much monetary policy can do to improve it.

But there’s a problem here. The law of the land requires the Fed to care about interest rates. Even if economists are right about the redundancy of the interest rate plank, nobody elected them to write the nation’s laws. You can’t substitute the judgment of a few macroeconomic experts for that of elected legislators without violating the democratic process.

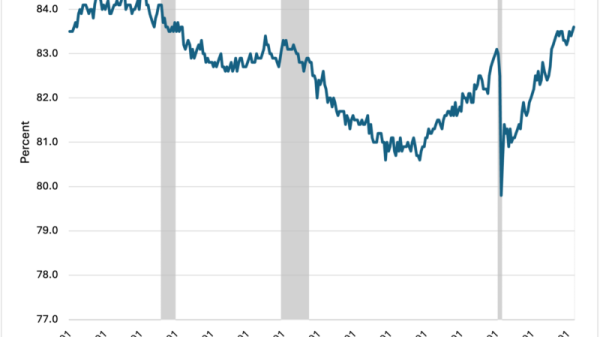

Furthermore, the reasoning behind the alleged irrelevance of interest rates proves too much. The same arguments also imply the Fed shouldn’t care about employment! Everything we said about capital markets also applies to labor markets. Supply and demand for labor finds the right balance between additional benefits and costs of working. The Fed does all it can for workers by focusing on price stability. If we truly believe the interest rate plank is redundant, logic compels us to come to the same conclusion about the employment plank.

The Fed has just as much reason to start ignoring the employment plank as it has for ignoring the interest rate plank in recent decades. If the central bank announced it would henceforth interpret the employment and interest rate parts of its mandate as fully covered by the price stability part of its mandate, you can bet economists, public intellectuals, and policy experts would raise a stink. For some reason, everyone views promoting employment as more important than stabilizing interest rates. Something tells me this reflects political biases more than reasoned reflection.

Fortunately, there’s a way around this dilemma. We can improve Fed policymaking while also respecting basic democratic norms. The solution is to amend the Federal Reserve Act once more. The economists are, in fact, right about the irrelevance of the interest rate plank. They would also be right about the irrelevance of the employment plank if they would only follow their logic to its necessary conclusion. It’s time to end the capital-labor asymmetry by striking these parts of the Fed’s mandate.

But economic theory, even good economic theory, does not deserve citizens’ obedience. Duly ratified law does. Hence, democratically accountable legislators should narrow the Fed’s goal to price stability only.

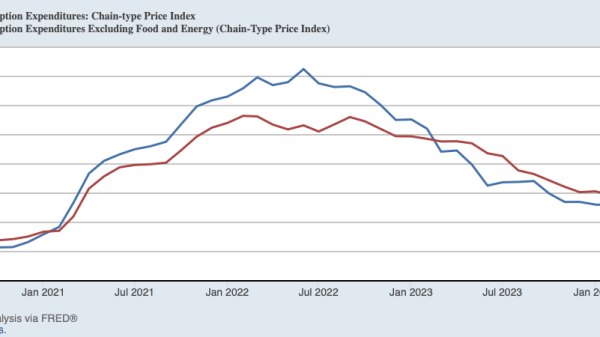

This shouldn’t be a hard sell, politically. We’re less than three years out from crippling inflation. Prices during the summer of 2022 were rising at almost 10 percent per year. Even now, Americans are hopping mad about high prices. Eggflation, anyone? While many of these prices reflect non-monetary factors, the overall level of prices is much higher than it would have been had the Fed not overreacted to COVID-19. Frankly, it’s an indictment of our elected representatives—especially the Republicans, who campaigned on this—that they haven’t already refocused the Fed on one of the few things it can control.

Central banking as a matter of law conflicts with central banking as a matter of policy. Resolving the tension is hopeless unless we both change the relevant statutes and stop selectively applying the economic way of thinking. Let’s fix both problems by making the Fed responsible for stable prices alone.